(Keller 7, 8, 9)

Probability distributions

(Keller 7, 8)

A probability distribution is a table, formula or graph that describes the values of a random variable and the probability associated with these values. Since a random variable can be either discrete or continuous we have two types of probability distributions: discrete and continuous probability distributions.

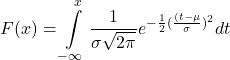

An example of a formula as distribution function is the following continuous normal distribution function.

An example of a table is the following table which describes a discrete distribution function.

| Number of persons | Number of households |

|---|---|

| 1 | 31.1 |

| 2 | 38.6 |

| 3 | 18.8 |

| 4 | 16.2 |

| 5 | 7.2 |

| 6 | 2.7 |

| 7 or more | 1.4 |

| Total | 116.0 |

Discrete probability distributions

(Keller 7)

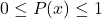

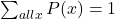

The following requirements hold for the the probability ![]() :

:

for all

for all

There is a relation between the relative frequency diagram and the discrete probability function.

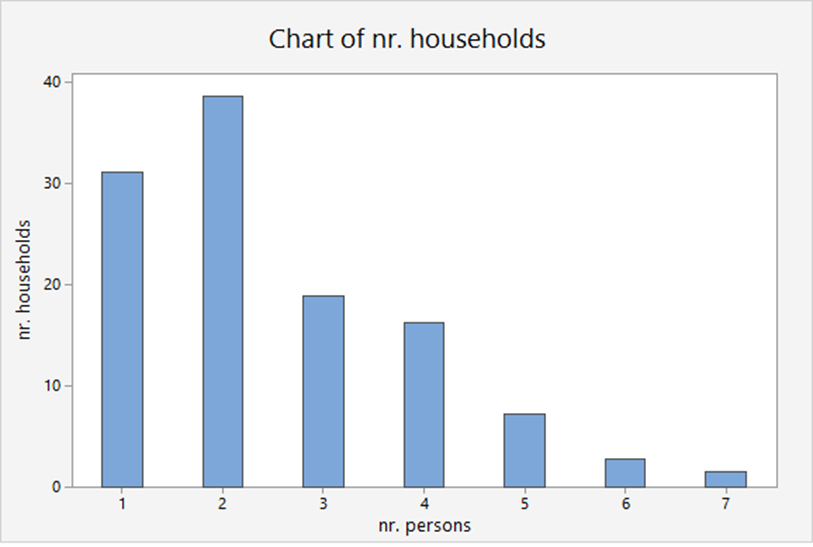

Distribution of the households

The probability distributions can be estimated from relative frequencies.

![]() is a discrete variable, the number of persons in a household.

is a discrete variable, the number of persons in a household.

| X | # households millions | P(x) |

| 1 | 31.1 | .268 |

| 2 | 38.6 | .333 |

| 3 | 18.8 | .162 |

| 4 | 16.2 | .140 |

| 5 | 7.2 | .062 |

| 6 | 2.7 | .023 |

| 7 or more | 1.4 | .012 |

| Total | 116.0 | 1.00 |

![]() is the discrete probability distribution of the number of persons in a household.

is the discrete probability distribution of the number of persons in a household.

We have: ![]() , etc.

, etc.

Also we can compute ![]()

Population mean E(X)

(Keller 7)

The population mean ![]() is the weighted average of all values of

is the weighted average of all values of ![]() . The weights are the probabilities.

. The weights are the probabilities.![]() is called the expected value of

is called the expected value of ![]() and is defined by the following formula.

and is defined by the following formula.

![]()

Example: a dice

What is the mean of throws of a fair dice.?![]()

![]() for all

for all ![]()

and thus:![]()

Population variance V(X)

(Keller 7)

The population variance ![]() is calculated similarly. It is the weighted average of the squared deviations from the mean

is calculated similarly. It is the weighted average of the squared deviations from the mean ![]() . The weights are the probabilities. It is defined by the following formula:

. The weights are the probabilities. It is defined by the following formula:

![]()

Example: distribution of households![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The standard deviation is ![]() .

.

Covariance of two discrete variables

The covariance of two discrete variables ![]() and

and ![]() is defined as:

is defined as:

![]()

![]() is the joint probability distribution of the random variables

is the joint probability distribution of the random variables ![]() and

and ![]() :

: ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Note. We also write ![]() .

.

Laws of E(X) and V(X)

(Keller 7)

![]()

![]()

![]()

These formulas can easily be derived from the definition of ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

These formulas can easily be derived from the definition of ![]()

For example: ![]()

Laws about sum of variables

(Keller, p. 234 (![]() and

and ![]() are two random variables)

are two random variables)

![]()

![]()

If ![]() and

and ![]() are independent then

are independent then ![]() and thus:

and thus:

![]()

Example

If ![]() and

and ![]() are independent then (because

are independent then (because ![]() and

and ![]() :

:![]()

![]()

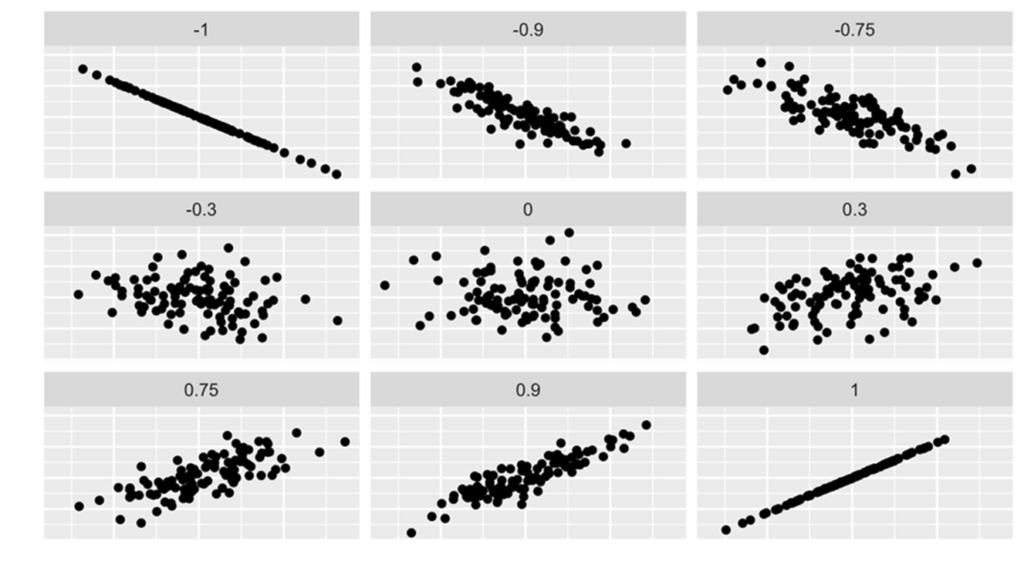

Coefficient of correlation

The coefficient of correlation is defined as the covariance divided by the standard deviations of the variables.

The population coefficient of correlation is:

![]()

The sample coefficient of correlation is:

![]()

The coefficient of correlation answers the question: how strong is the association between ![]() and

and ![]() ?

?

The advantage of the coefficient of correlation over the covariance is that it has a fixed range from ![]() to

to ![]() (proven by Mathematics). If the two variables are very strongly and positively related, the coefficient value is close to

(proven by Mathematics). If the two variables are very strongly and positively related, the coefficient value is close to ![]() (strong positive linear relationship). If the two variables are very strongly and negatively related, the coefficient value is close to

(strong positive linear relationship). If the two variables are very strongly and negatively related, the coefficient value is close to ![]() (strong negative linear relationship). No straight linear relationship is indicated by a coefficient close to 0.

(strong negative linear relationship). No straight linear relationship is indicated by a coefficient close to 0.

The following graphs depict the relations of ![]() and

and ![]() for various coefficients of correlation, varying from

for various coefficients of correlation, varying from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

Binomial distribution

(Keller 7)

The binomial distribution is the probability distribution that results from doing a binomial experiment. Binomial experiments have the following properties:

- There are a fixed number of trials, represented as

- Each trial has two possible outcomes, success or failure

;

;  for all trials

for all trials- The trials are independent, meaning that the outcome of one trial does not affect the outcomes of any other trials.

The binomial random variable ![]() counts the number of successes in

counts the number of successes in ![]() trials of the binomial experiment.

trials of the binomial experiment.

(e.g. s s f s f f f s f s s f s shows ![]() trials and

trials and ![]() successes).

successes).

To calculate the probability associated with each value ![]() we use combinatorics:

we use combinatorics:

![]() for

for ![]()

Example

A quiz consists of ![]() independent multiple-choice questions (

independent multiple-choice questions (![]() ). Each question has

). Each question has ![]() possible answers, only one of which is correct (

possible answers, only one of which is correct (![]() ). You choose to guess the answer to each question.

). You choose to guess the answer to each question. ![]() is the number of correct guesses

is the number of correct guesses ![]() . The probability that you will have a score

. The probability that you will have a score ![]() is:

is:

![]()

{![]() is called

is called ![]() factorial

factorial ![]() ;

; ![]() ;

; ![]() )

)

Mean and variance

(Keller 7)

The mean, variance and standard deviation of a binomial random are variable (can be derived mathematically):

![]()

![]() and thus:

and thus:

![]()

Continuous random variables

(Keller 8)

Unlike a discrete random variable, a continuous random variable is one that assumes an uncountable number of values. We cannot list the possible values because there is an infinite number of them. Because there is an infinite number of values, the probability of each individual value is ![]() . So, the probability that a man has a height of exactly 180 cm is:

. So, the probability that a man has a height of exactly 180 cm is:

![]()

Pobability density functions

{Keller 8)

A function ![]() is called a probability density function (over the range

is called a probability density function (over the range ![]() ) if it meets the following requirements:

) if it meets the following requirements:

![]() for all

for all ![]()

The total area between curve and ![]() -axis is:

-axis is:

![]()

For the interval [a, b] we may also take ![]() , as is the case in e.g. the normal distribution.

, as is the case in e.g. the normal distribution.

The normal density function

(Keller 8)

The normal distribution is the most important of all probability distributions. The probability density function ![]() of a normal random variable

of a normal random variable ![]() is given by:

is given by:

![]() for

for ![]()

The graph is bell-shaped and symmetrical around the mean ![]() . This density function is also denoted by

. This density function is also denoted by ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

The normal distribution function is defined by:

![]()

Therefore, the probability ![]() equals

equals ![]() .

.

This infinite integral cannot be computed analytically (pen and paper), therefore we need a table or a computer can do the job.

Standard normal distribution

(Keller 8)

A normal density function with mean ![]() and standard deviation

and standard deviation ![]() is called the standard normal density.

is called the standard normal density.

![]() for

for ![]()

Any normal distribution can be converted to a standard normal distribution, see below. The standard normal distribution is also denoted by ![]() .

.

Any (normal) variable ![]() can be converted to a new (normal) variable

can be converted to a new (normal) variable ![]() :

:

![]()

with the following properties:

![]()

![]() .

.

Thus, if

![]()

then

![]() .

.

Example

Suppose the demand ![]() is a normally distributed variable with mean

is a normally distributed variable with mean ![]() and standard deviation

and standard deviation ![]() and we want to compute

and we want to compute ![]() . Then:

. Then:

![]()

![]()

![]() .

.

The answer can be found in Table 3 of Appendix B9 of Keller, or by Excel.

Other continuous distributions

There are three other continuous distributions which will be used later.

distribution (also called Student's

distribution (also called Student's  distribution)

distribution) (ci-squared) distribution)

(ci-squared) distribution) distribution

distribution

Sampling distributions

(Keller 9)

A sample of size ![]() is just one of many possible samples of size

is just one of many possible samples of size ![]() . If

. If ![]() is the population size and

is the population size and ![]() the sample size (

the sample size (![]() ≪

≪![]() ) then the number of possible different samples equals

) then the number of possible different samples equals ![]() .

.

They are usually very large, e.g.: ![]()

Most samples have (different) random statistics, e.g. ![]() or

or ![]() .

.

These sample statistics have a probability distribution, the so-called sampling distribution.

Some mathematics

![]() and

and ![]() are sample statistics. Let us derive the distribution function of

are sample statistics. Let us derive the distribution function of ![]() . We know that

. We know that ![]() and

and ![]() . Then:

. Then:

![]()

![]()

![]()

So, for ther random variable ![]() it holds:

it holds: ![]() and

and ![]()

Earlier we defined for any random variable ![]() :

:

![]()

and thus for the random variable ![]() we get:

we get:

![]()

Central Limit Theorem

(Keller 7, 8, 9)

The sampling distribution of the means of random samples drawn from any population is approximately normal for a sufficiently large sample size ![]() . The larger the sample size, the more closely the sampling distribution of

. The larger the sample size, the more closely the sampling distribution of ![]() will resemble a normal distribution.

will resemble a normal distribution.

If the distribution of the population is normal, then ![]() is normally distributed for all sample sizes

is normally distributed for all sample sizes ![]() . If the population is non-normal, then

. If the population is non-normal, then ![]() is approximately normal only for larger values of

is approximately normal only for larger values of ![]() . In most practical situations, a sample size of

. In most practical situations, a sample size of ![]() may be sufficiently large to allow us to use the normal distribution as an approximation for the sampling distribution of

may be sufficiently large to allow us to use the normal distribution as an approximation for the sampling distribution of ![]() .

.

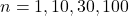

Verify Central Limit Theorem

(Keller 9)

The following is a program in pseudo code.

- Take a first sample of size

of a uniform distribution and compute its sample mean

of a uniform distribution and compute its sample mean  ;

; - Repeat this

times and thus get

times and thus get  sample means

sample means  . Also these means are random variables.

. Also these means are random variables. - According to the Central Limit Theorem these

random means should be (approximately) normally distributed.

random means should be (approximately) normally distributed. - Verify this graphically by drawing a histogram.

- Verify this by applying a normality test (e.g. Anderson-Darling).

- Repeat 1-5 for

and notice the differences.

and notice the differences.

The actual program is executed by the programming language but any programming language can do the job. Thc code of the R program is as follows:

# Suppose x has a uniform distribution

# n is the sample size, preferably n = 30

n <- 30

# k is the number of such sample means, sufficiently large, e.g. k = 5000

k <- 5000

# According to the Central Limit Theorem

# the k sample means should approximate a normal distribution

z <- numeric(k) # z is a vector with k elements and will contain all k sample means

for (j in 1:k) (z[j] <- mean(runif(n))) # compute the mean of each uniform sample

# show the histogram of these means

hist(z)

# and find out whether the distribution of means is normal

# which is approximately true for n ≥ 30

ad.test(z) # Anderson-Darling test

The result is as follows.

The left graphs represents a unoform distribution on ![]() ; the right graph depicts a histogram of

; the right graph depicts a histogram of ![]() sample means which is rather good approximation of a normal distribution.

sample means which is rather good approximation of a normal distribution.

Using the standard normal distribution

(Keller 9)

Suppose the population random variable ![]() is normally distributed with

is normally distributed with ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

We take a sample of size ![]() drawn from the population. The sample mean is denoted by

drawn from the population. The sample mean is denoted by ![]() . We want to compute

. We want to compute ![]() .

.

We know:

![]() is normally distributed, therefore so will be

is normally distributed, therefore so will be ![]() .

.

![]() and

and ![]()

![]() Let op: fout in formule.

Let op: fout in formule.

![]()

The answer can be found in Table 3 of Appendix B9 of Keller.

The difference of two means

(Keller 9)

Consider the sampling distribution of the difference ![]() of two sample means.

of two sample means.

If the random samples are drawn from each of two independent normally distributed populations, then ![]() will be normally distributed as well with:

will be normally distributed as well with:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let op: fout in formule.

If two populations are not both normally distributed, and the sample sizes are large enough (![]() ), then in most cases the distribution of

), then in most cases the distribution of ![]() is approximately normal (see the Central Limit Theorem).

is approximately normal (see the Central Limit Theorem).

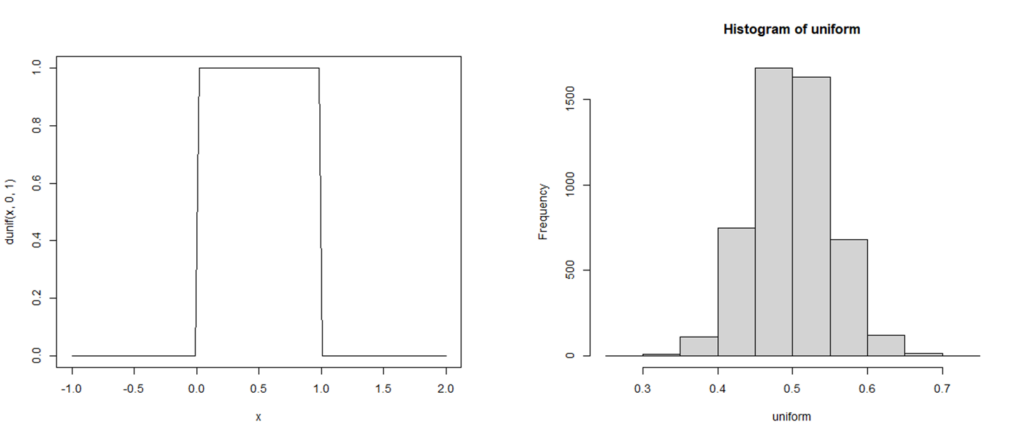

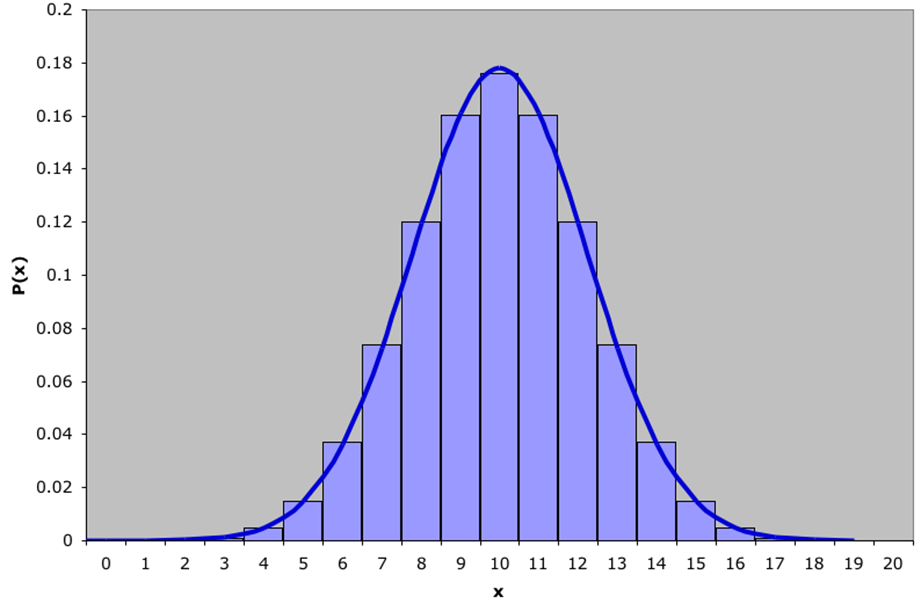

Normal approximation to Binomial

See the following example: a binomial distribution with ![]() and

and ![]() superimposed by a normal distribution (

superimposed by a normal distribution (![]() and

and ![]() ).

).

The graph shows ![]() and the graph of a

and the graph of a ![]() distribution. See the formulas of the probabilities of a binomial distribution.

distribution. See the formulas of the probabilities of a binomial distribution.

The normal approximation to binomial works best when the number of experiments ![]() is large and the probability of succes

is large and the probability of succes ![]() is close to

is close to ![]() .

.

For the approximation to provide acceptable results two conditions should be met:

![]() and

and ![]()

The following graph shows the approximations witp ![]() and various values of

and various values of ![]() .

.

Example

For a binomial distribution (![]() we find (using Excel):

we find (using Excel):![]() .

.

For a normal distribution (![]() ) we find:

) we find:![]() (continuity correction).

(continuity correction).

Distribution of a sample proportion

The estimator of a population proportion of successes is the sample proportion. That is, we count the number of successes in a sample of size ![]() and compute:

and compute:

![]()

![]() is the number of successes,

is the number of successes, ![]() is the sample size.

is the sample size.

Note that the random variable ![]() has binomial distribution.

has binomial distribution.

Using the laws of expected value and variance, we can determine the mean, variance and standard deviation. Sample proportions can be standardized to a standard normal distribution using the formula:

![]() and thus

and thus ![]()

Note.

Binomial disribution: ![]()

![]()

![]()

and thus:

![]()

Example

In the last election a state representative received ![]() % of the votes (so

% of the votes (so ![]() ; this can be considered as a population parameter!)

; this can be considered as a population parameter!)

One year after the election the representative organized a survey that asked a random sample of ![]() people whether they would vote for him in the next election.

people whether they would vote for him in the next election.

If we assume that his popularity has not changed what is the probability that more than half of the sample would vote for him?

The number of respondents who would vote for the representative is a binomial random variable with ![]() and

and ![]() and we want to determine the probability that the sample proportion is greater than

and we want to determine the probability that the sample proportion is greater than ![]() %, That is, we want to compute

%, That is, we want to compute ![]() .

.

From the foregoing we know that the sample proportion ![]() is approximately normally distributed with mean

is approximately normally distributed with mean ![]() and standard deviation

and standard deviation ![]()

Thus we compute:

![]()

![]()

![]()

If we assume that the level of support remains at ![]() % the probability that more than half the sample of

% the probability that more than half the sample of ![]() people would vote for the representative is

people would vote for the representative is ![]() %.

%.